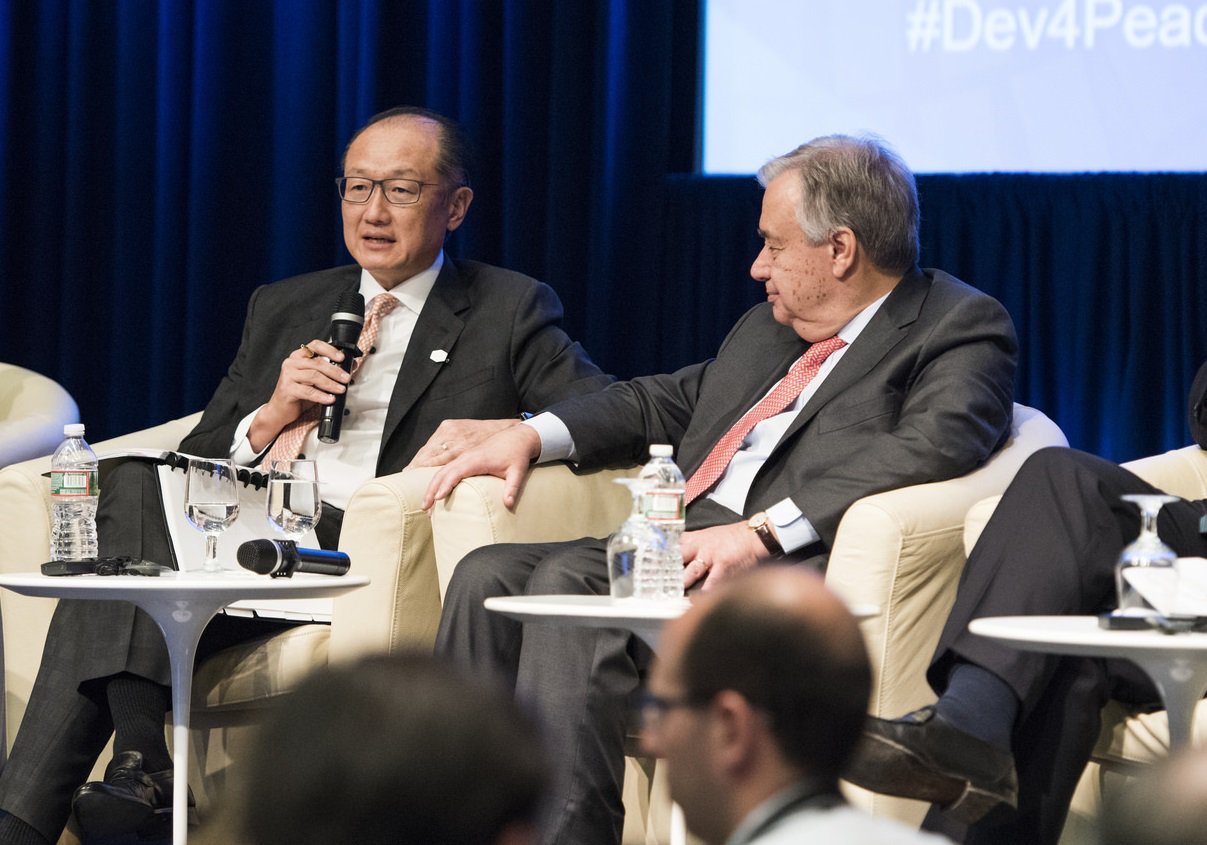

Last week the United Nations (UN) and World Bank launched ‘Pathways for Peace: Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict’. This ambitious new report is the first joint publication of its kind between the UN and World Bank, described in the report's foreward by Secretary-General Antonio Guterres and Jim Yong Kim, President of the World Bank, as 'a first step in working jointly to address the immense challenges of our time.'

On 12 March the authors of the report, as they continue their tour around Europe, visited ODI for a closed discussion. Afterwards, we asked three ODI conflict and peacebuilding experts for their take on the implications, challenges and opportunities ahead for this landmark report.

Frequently asked questions

Alex Thier: the good and bad news

As the world debated a new set of sustainable development goals in 2015, the one most missing from previous goals was also the most contested: the quest for just, peaceful, and inclusive societies. The experience of the previous two decades had demonstrated that rapid progress could be made to advance human development and pull people out of poverty – if they avoided violent conflict.

Yet conflict – and the death, displacement, economic decline, extremism, and lost generations that follow – is rising around the world after years of decline. Much more challenging than delivering vaccines and textbooks, preventing and ending conflict is extremely complex, taking multiple generations and complete local ownership.

A powerful new joint report from the United Nations and the World Bank makes a compelling case that we must invest in justice, inclusion, and effective institutions to help societies to recover from and avoid violent conflict. The bad news is that we aren’t doing or investing nearly enough. And it is costing us dearly. The business case for prevention in the report estimates the potential for $33bn to $70bn in annual savings. The human costs, and risks, of course, are much greater.

The good news is that there is evidence that it works. Examples from Bosnia, Kenya, and Nepal show the success of long term processes that address grievances, create economic and political opportunities, and build processes and institutions that can read and respond to warning signs. Conflicts like those in Yemen, South Sudan, or Afghanistan are not inevitable or insoluble. Indeed, the evidence shows that we can’t afford not to work with partners in those societies at risk of conflict to find a just and sustainable peace.

Frequently asked questions

Mareike Schomerus: what does inclusion mean?

The United Nations and World Bank report will undoubtedly become known as the ‘Pathways for Peace’ report. But it’s to the subtitle that I think we ought to pay more attention: ‘Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict.’ It sums up the main message, but also the greatest challenge.

Inclusion, and its nemesis exclusion, are centre stage here. Inclusivity anchors every attempt at building peaceful societies. Excluding groups is very much identified as a pathway to violent conflict. The report argues that a general shift towards ‘more open political systems’ allows for ‘demanding’ such inclusion. It stresses the need for processes to be inclusionary, outlines that inclusion can be economic, social or political and that it can mean that groups (such as women or young people) are included in daily life in ways they were not before.

SLRC research, which informed the report, shows that being heard matters for how people experience their lives, even if things don’t always change after a grievance is voiced. And yet, the exact nature of inclusivity remains something of a black box. Inclusion, of course, also means giving something up: To include someone new, someone else has to renounce a piece of the cake they once held. This is the hard part. And sometimes, inclusion of identity-based groups risks further division and fragmentation. Does power sharing help inclusion in the long run? Sometimes it does, sometimes it doesn’t.

And maybe most importantly, we know far too little about how individuals experience their own inclusion or exclusion. What are the processes that lead people to experience inclusion and to feel treated fairly? This is one of the huge questions that the report throws open. ‘Pathways for Peace’ highlights the importance of the principle. Now we need to find ways of understanding inclusion much better.

Frequently asked questions

Sara Pantuliano: delivering the UNSG’s prevention vision

The United Nations Secretary-General’s (UNSG) vision that ‘prevention should permeate everything we do’ requires the UN to re-embrace its founding role: to save future generations from the scourge of war.

Delivering on Pathways for Peace will be a challenge within the current UN system. There are many things holding back its realisation, including a limited culture of prevention, inadequate coordination and leadership, the failure to simplify administrative systems and processes to support field-level action, and Member States’ hesitation to embrace a more proactive prevention role.

The inability of Member States to resolve major crises significantly constrains the UN’s prevention work. The conflation of the authority and capacity of Member States with the will and capacity of the Secretariat – and other UN entities – also distorts perceptions of the UN’s effectiveness. However, when Member States have empowered the UN system to act, it has been able to make good use of its prevention capacities, staving off crises. In 2016, in The Gambia for example, the UN supported African leaders to work together mobilising pressure for a peaceful post-election transition of power.

Many within and beyond the UN have confidence that the UNSG’s assertive leadership and creativity will allow his vision to come to light, provided Member States overcome their resistance and enable the UN to act more effectively. But the support of Member States will not be enough. For the UN to become more effective at preventing crises, three key things need to happen.

The UNSG needs to ensure that there are credible, high-quality and accountable leaders who will introduce and drive a culture of prevention both at HQ and in country operations. The Secretariat, Agencies, Funds and Programmes must overhaul systems and processes to pool existing financial and human resources more effectively towards prevention priorities. Finally, the UN must act as a catalyst for others on crisis prevention – emphasising partnerships while reflecting on its limitations and comparative advantages on a case-by-case basis.

A culture shift is critical if the UNSG’s vision is to become reality. With 16 of the 17 SDG goals and 35 SDG targets related to prevention, Agenda 2030 can serve as a framework to promote collaboration on prevention and discourage the fragmented, competitive habits of individual UN entities.